Lexos Discovers the Grapefruit Diet

Overview and Getting Started with Lexos

Lexos is an open-source tool for corpus cleaning and analysis built by the Lexomics Research Group at Wheaton College. I am using the browser-based version, but there is also a version available for local installation.

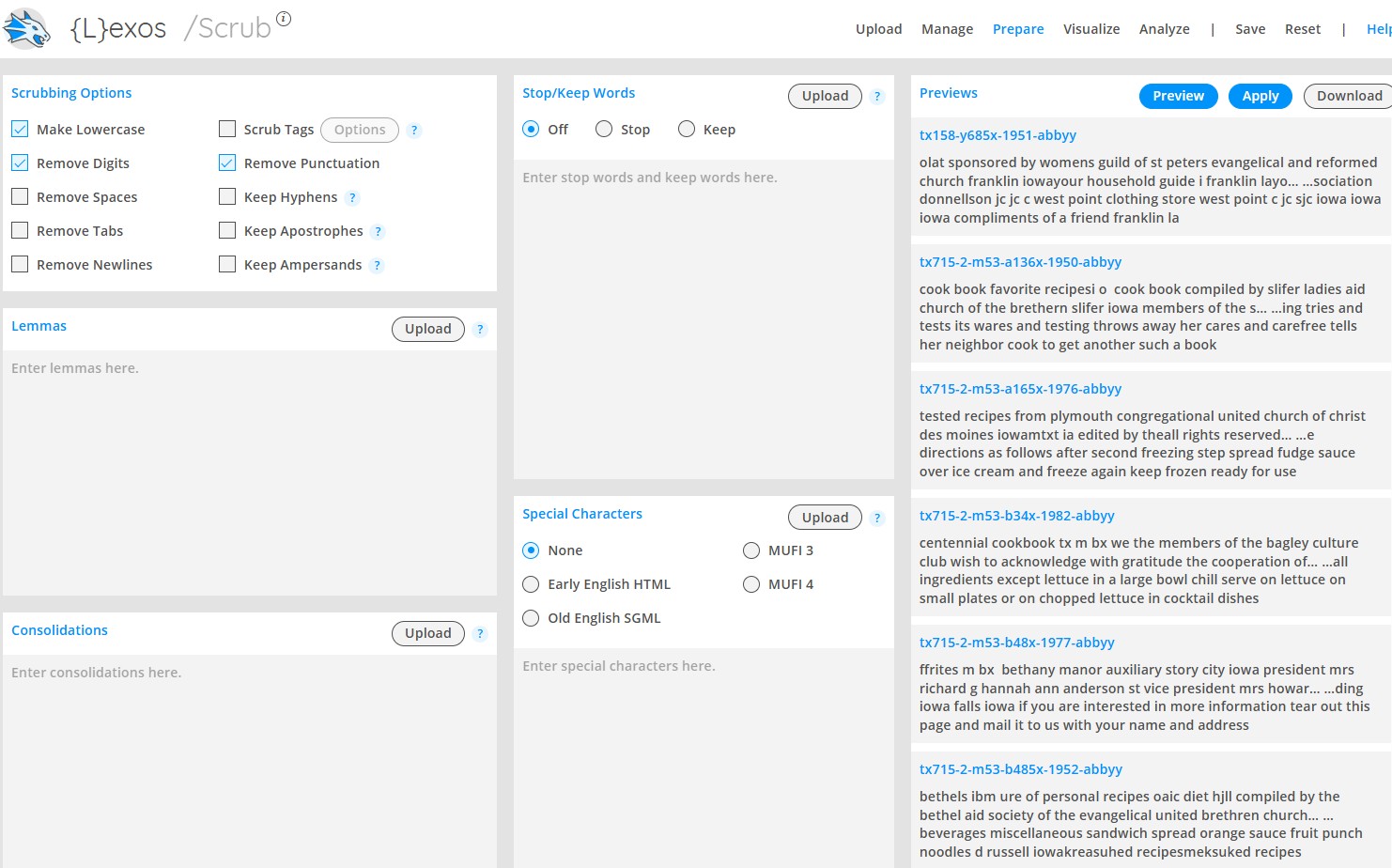

Lexos provides several options for cleaning and normalizing your data prior to your analysis. Using the Scrub tool you can remove punctuation, numbers, and spaces, lowercase all text, remove a defined list of stop words and import rules for handling special characters. For this corpus, I removed punctuation and digits and made all lowercase. I also uploaded a standard set of stop words from the Natural Language Toolkit to remove common words like “the,” “and,” “is,” etc.

Once you’ve applied all desired cleaning steps you can either export your cleaned corpus for use in another tool, or use it to explore a variety of visualization and analysis options within Lexos including word clouds and bubble graphs as well as dendrograms, k-means clustering, and cosine similarity measures.

Top Words Analysis

One of Lexos’ features that I found most useful and have chosen to explore further is the Top Words tool. Top Words allows you to compare each individual document to the corpus as a whole to determine which words are unique to particular texts. You can choose to tokenize by tokens, characters, or n-grams and you can make a few adjustments to the number and frequency of terms to compare. If you’ve clustered your texts into what Lexos calls “classes” you can also compare each class of texts to all others, an option that I’ll be exploring in a later post.

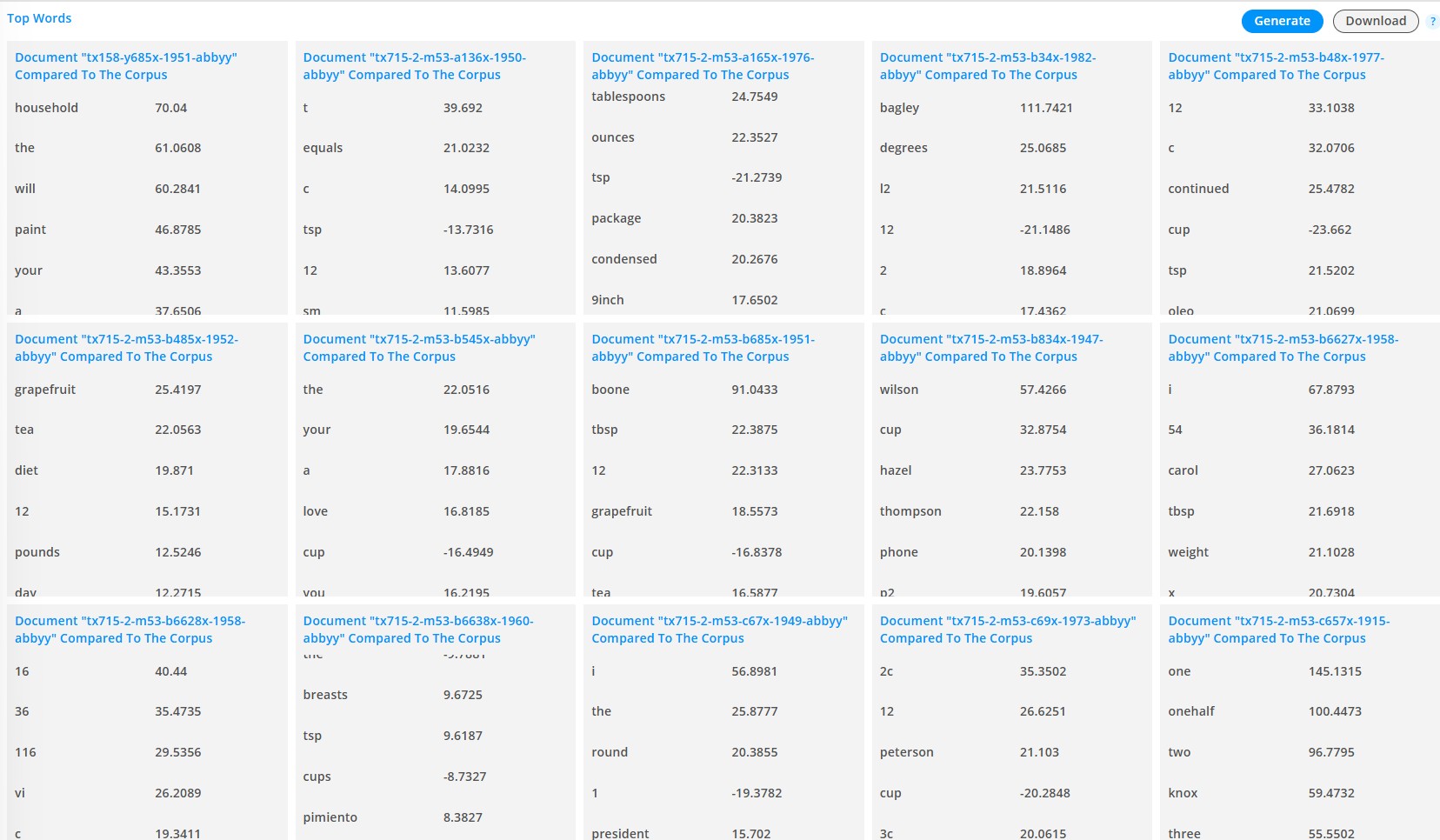

To begin, I chose to compare each document to the corpus by unigram tokens. I noticed that running the tool with no frequency limits took a very long time, so I chose to limit the analysis to the top 1,500 terms rather than all terms. Lexos will output the top words for each text to a grid on the screen, but I chose to export the results to csv in order to get a better look. Terms with higher positive numbers occur more frequently compared to the corpus as a whole, and higher negative numbers occur less frequently compared to the corpus as a whole. There are a lot of questions to explore in looking at the results, so I’ll share just one here that was particularly interesting to me.

Why so much grapefruit?

Amid the large spreadsheet of numbers, I noticed what seemed like an unusual number of books with high proportions of the word “grapefruit” compared to the corpus - five books to be exact. Grapefruit is not a common recipe ingredient, and while this analysis is meant to highlight unique words within specific books, I would have expected perhaps one or two “grapefruit” books, but not five. Why all the grapefruit?

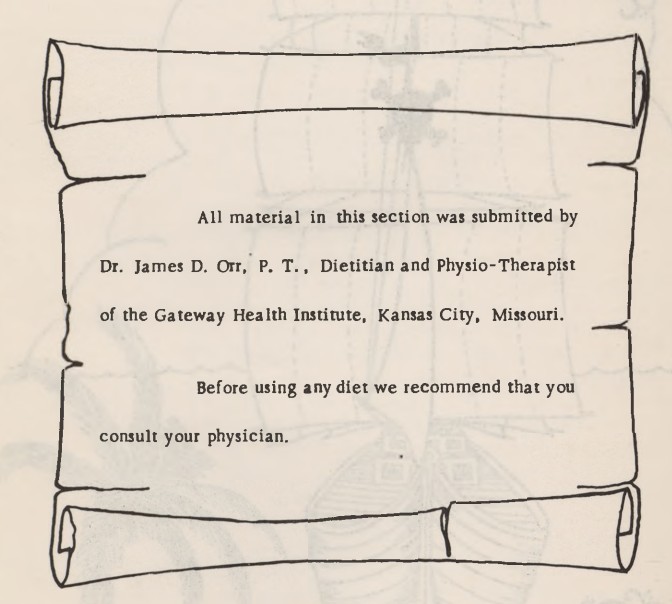

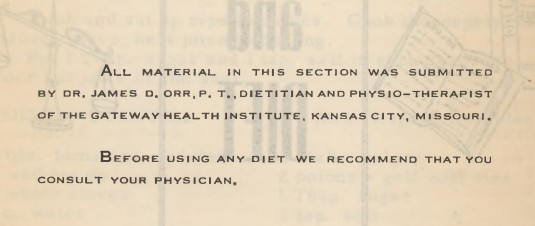

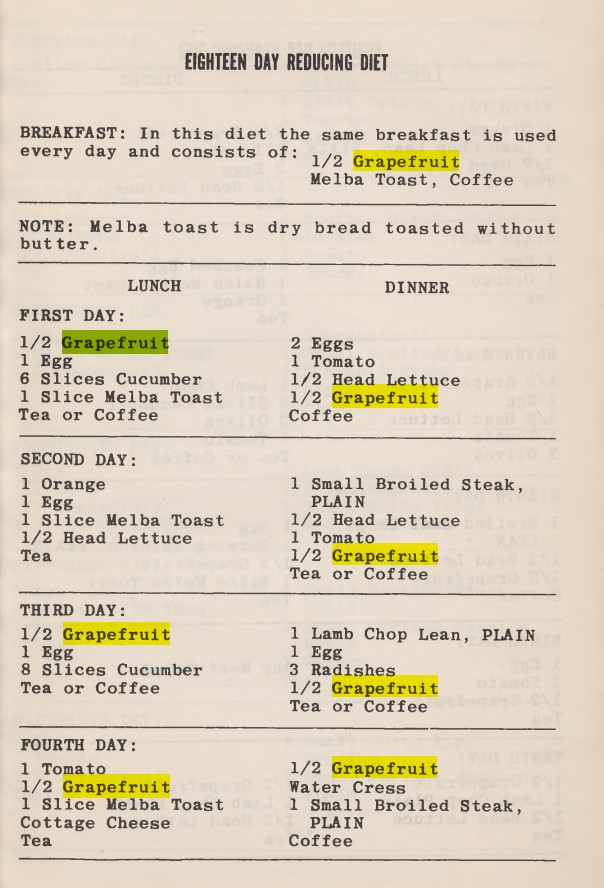

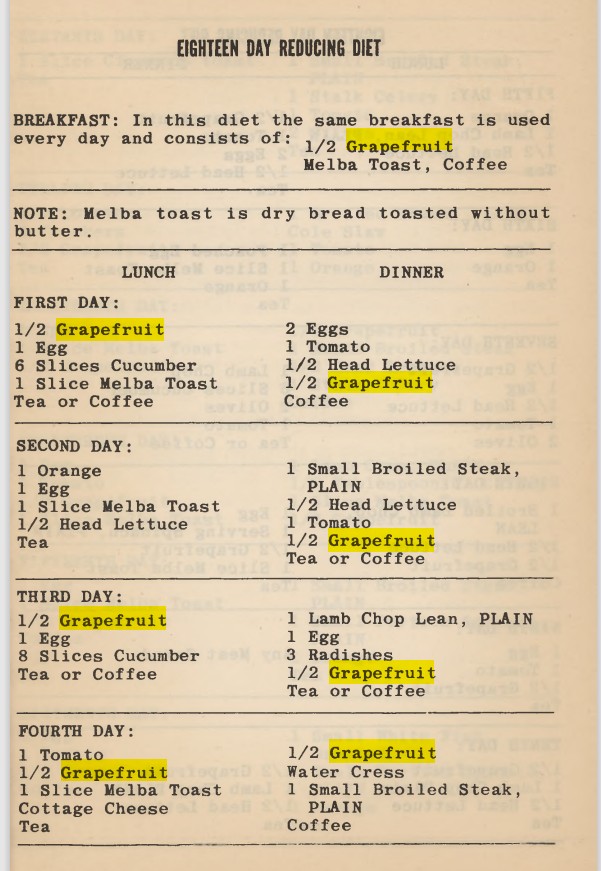

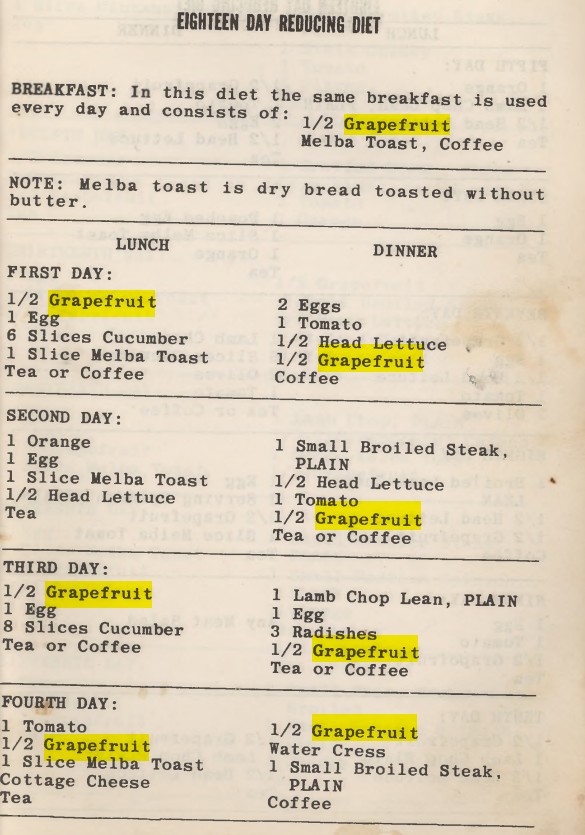

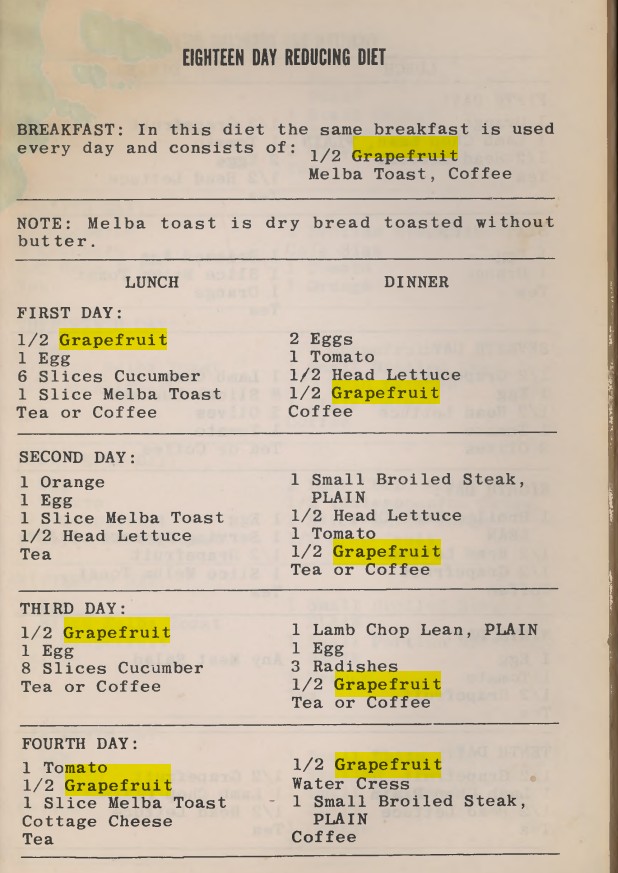

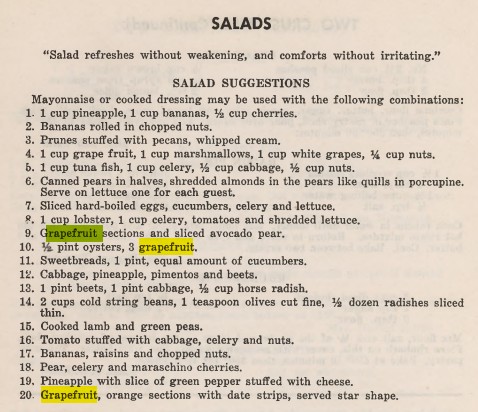

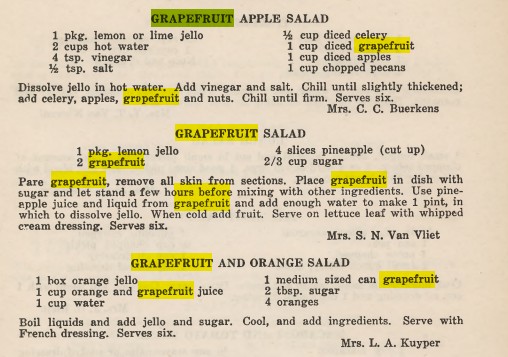

The answer was quickly discovered upon viewing the digitized cookbooks, but I think the results demonstrate the value of this type of exploratory text analysis and are therefore worth sharing. I opened the first pdf, hit “ctrl-f” for “grapefruit,” and found all 31 mentions of grapefruit clustered in one section, the diet section. Three more cookbooks after that contained the exact same section produced by the exact same Dr. Orr. The “18-Day Reducing Diet,” also known as the Hollywood Diet and more commonly, the Grapefruit Diet, includes one grapefruit half with every meal for 18 days. This diet became popular in 1930s Hollywood before spreading across the U.S. and reamerging several times in different forms throughout the twentieth century. It is fairly common in community cookbooks to see standard sections of nutrition, measurements, ingredient substitutions, and household tips contributed by the publisher in addition to the community-contributed recipes. These diet sections appear to be this same type of publisher-contributed section.

Three of the four books are from the late 1940s and early 1950s, but one book has the date 1910 in the call number which seemed out of place considering it contained the identical diet pages of the other books. To investigate this, I looked at the catalog record for this book which actually states “between 1910 and 1940?” in the Creation Date field, most likely an approximation based on the look and content since the book does not have a printed date. In this case, I think we can assume the book is from around the time of the other 3 books (~1948-1952) given the inclusion of identical diet information and even an identical image and layout to the 1952 Bethel book.

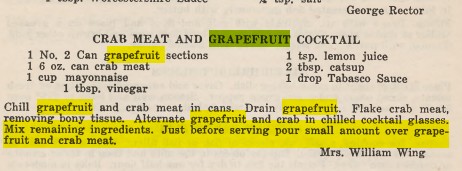

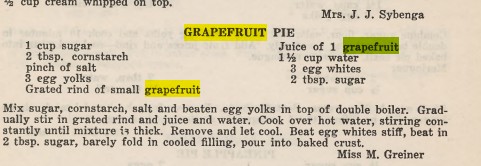

One additional book had a similarly high proportion of “grapefruit” occurrences but did not contain this same diet section. It turns out the folks in Pella just really like grapefruit! Grapefruit pie, anyone?

In a future post I will dive deeper with Lexos to identify clusters of similar cookbooks using the K-Means tool and investigate what makes each cluster unique with the “classes” comparison in the Top Words tool. Stay tuned!